NEWS

My Church, and Memories: They Do Come Again

By Eva Gasperich

From the Evening Capital

Tuesday, September 9, 1958

Dcn. David and I were rummaging through the water closet the other day and found a poster board with an old article about St. Paul’s Chapel that ran in the Evening Capital on Tuesday, September 9, 1958 by a woman named Eva Gasperich. We thought it was so neat to have a firsthand account of some of the history at St. Paul’s and wanted to share it with you. Here it is:

In the rugged days of early Anne Arundel, people went to unheated churches and worshipped God on their knees on cold, bare floors. They read the Holy Bible daily, studied their church catechism and prayed out loud in the family circle night and morning.

In Anne Arundel county St. Anne’s in Annapolis was the center of the Protestant Episcopal faith. But the rough dirt roads caused country people great hardship to attend. in order to be on time for Morning Prayer, they had to drive to Annapolis with horse and carriage the day before, and put up over night. to alleviate this situation, sometime in 1730, the Episcopal Diocese had a chapel erected in the North Severn River area on the old Chesterfield Road and called it the Chapel of Ease.

For 77 years hereafter this chapel served the simple needs of the few country Episcopalians, scattered through Severn Parish. Then on a warm Whitsunday a great wind-storm swept in from South River to the Severn and destroyed the Chapel of Ease. A tablet, erected by the Daughters of the Revolution, now marks this old site.

Meanwhile, Francis Asbury, the famous circuit rider who followed the Wesleyan movement from the Episcopal Church, and was the first Methodist Bishop in America, had established special headquarters at Brooksy’s Point on the Severn River, called Asbury’s Station. This also is marked by the D.A.R.

When the Chapel of Ease blew down, one William Thomas Turner, with an inspiration for Christian unity, offered a piece of his property called Warfield’s Plains at Severn Cross Roads for a community church to be jointly built and shared by Methodists and Episcopalians. The sects were financially hard pressed and few in numbers in those days.

This plan was gratefully accepted. The elders met and planned. Every man who could handle a saw and an axe came forward to work. What financial resources the two denominations could muster were pledged.

When the first church opening was held, both denominations took part. The sermon of the day is attributed to Francis Asbury.

It was a stupendous event for many sociable helpful years afterwards Methodists and Episcopalians held alternate services in this building. It was called Old Cross Roads Church. Ivy-covered brick Baldwin Memorial stands there now facing on the General’s Highway.

As times advanced and the population increased, the Episcopalians, let by Basil Hall, who lived nearby, separated from Old Cross Roads Church. Three miles further down on Chesterfield road the Episcopal element built a brick church fired from a clay field opposite the side and named it St. Stephens. This was sometime in 1843.

Severn Parish was then formally separated from St. Anne’s. The Methodists bought out the Episcopal interests in Old Cross Roads. The proceeds were set aside for a chapel fund.

At Crownsville Station of the Annapolis and Elkridge steam railroad, there was a corral in a grove where people taking the train tied their horses. This lot was owned by two spinster gentlewomen named Brown. They were weary of travelling over awful roads in a creaking carriage either to St. Anne’s or St. Stephen’s and offered the old corral to Severn Parish upon which to build a mission chapel. With the funds from the sale of Episcopal interests in Old Cross Roads Church, and pledges from the country faithful, St. Paul’s Chapel was build in the livestock grove at Crownsville in 1850, when Maryland was sorely troubled by the War Between the States.

It was a small frame structure, but Gothic-styled, with steeple and bell and it was hand-hewed, with 16 pitch-pine pews, including four in the slave gallery at the rear. On either side of the steps to the front vestibule, there were smooth chestnut stumps placed where ladies on horseback might alight and mount with ease at the church entrance. Hitching rings were attached to the trees. At the rear of the church was a small carriage shed for the minister’s convenience. Attached to the shed was a vine-covered wooden outhouse divided discreetly in two sections, one for ladies, the other for gentlemen. A little way down under the bank near the Annapolis and Elkridge Railroad tracks, there was a flowing spring where a wooden bucket and a drinking gourd were kept for the thirsty. Here churchgoers filled pewter pitchers with fresh water for baptisms and the minister’s ablutions in the vestry.

Severn Parish in 1860 was pleased with the little new mission, set so conveniently between the railroad tracks and the public road from Baltimore to Annapolis, the very same road traveled alternately by the Continental and British armies during the early makings of America. Along this road the seed of the golden gorse of Scotland, let as waste, had sprouted, rooted and was blooming in profusion. To this very day the colors of Scotland are found in bloom in the Springtime.

St. Paul’s Chapel still stands there, exactly as first built, but the railroad tracks are gone, and the historic road winding by is hard-surfaced now and is known as The General’s Highway. This was the route taken by General of the Continental Army, George Washington, when he went to Annapolis to resign his commission.

It was in a time of tribulation that St. Paul’s Chapel was built at Crownsville. The first services were a prayer for peace between the States. And when the sad years were over, the parishioners gathered there to give thanks for the end of strife and to mourn the dead.

By not seceding Maryland was spared much of the savagery of conflict but sympathies were divided and hearts were torn. The Annapolis and Elkridge trains chugged by daily with soldiers and supplies for the front. Union soldiers patrolled the road and checked the congregation at worship.

At St. Paul’s Chapel the old families have gathered regularly by twos and threes throughout the years. Here they were baptized, confirmed, married, buried. Through the course of evolving times, dramatic changes have taken place in the countryside, but St. Paul’s Chapel remains the same, no alterations, no additions, still painted a spotless white inside and out. There are the same pitch pine pews, but now they are bright with new varnish, and the same heavy marble baptismal font stands at the rear. There is the same lectern with the old King James Bible; the same little altar with the single stained glass window inscribed in memory of a Rev. Hugh Maycock, and a window. undated, a name unknown, but a constant reminder of someone who long ago had stood for something very sacred in the sight of God.

The only new object is a Hammond organ—lately bought.

St. Paul’s always has a country fair and farm supper in the old grove when the corn is ripe. And then they come home again, the descendants of the founding families, from far and near, to sit and chat and sup in the shade and hear the roundelay of the mocking bird.

The new rector[1] who came to Severn Parish in 1910 was a man of great talents. He had served brilliantly in a large city parish, but his days were numbered with an incurable ailment. The time he had left he devoted to the people of his new parish. Tall, emaciated, but dynamic, his sermons struck like a thunderbolt in this farm neighborhood. The churchmen soon found out he was high church as well as an evangelist for our children. He invited every child of walking age to participate in his Sunday School and vested choir. Never before had there been such a fine choir or any high church ritual in Severn Parish. And the choir was composed of boys only! He was very firm about that. This electrified the parish. Many an indifferent Episcopalian, pleasantly relaxed over church attendance, perked up and came back to long-empty seats. St. Paul’s was thrilled and proud.

There were six Charles and Brice Worthington boys. The three Maynard Carr boys. Nine! Eight to walk two by two, and one to be the cross-bearer! Fair-haired Maynard Carr was chosen for cross bearer because of his fine looks. Full-throated Benjamin Skinner Carr was made the choir leader because of his beautiful appealing voice.

The ladies of the Guild who were the mothers of the boys made the choir vestments. They were ankle-length black cassocks with white linen capes and round turned down white linen collars tied with black silk bows. The 11 A.M. Easter Sunday service was selected for the choir’s premiere at St. Paul’s. The pastor trained his boys privately behind the closed doors of the chapel. Mrs. Brice Worthington, the organist, was the only outsider present at the rehearsals.

The mothers also made new altar cloths, white satin with heavy gold fringe and gold embroidery. Even the lectern had a new white and gold “throw,” and the old Bible a new white and gold “marker.” Local flowers bedecked the altar. Most of them were daffodils, the first flowers of spring to raise their golden trumpets to the Lord.

When the congregation entered St. Paul’s that Easter morning in 1910, they saw something new on the altar. Seven candles were glowing softly among the flowers below the stained glass window!

And all through the years that followed; between the burying and the marrying and the baptizing the survivors came back to the summer festival. Here reunion and farewell are steeped with laughter and hidden tears, and memory flashes bright with unforgettable faces.

“Alleluia! Alleluia! Alleluia!”

Our minister did not die a lingering death. This ardent high churchman died with merciful suddenness in an automobile crash a few years after 1910.

And in a grim time soon after, that choir of little boys were bearing arms in World War One. Benjamin Skinner Carr never came back. Only 18 years old, he was killed in the Argonne Forest in France on the 23rd of October, 1918 while leading a a machine gun squad in action. A placque dedicated to his memory hangs in the old chapel where he sang so happily that Easter in his boyhood. He is honored by the Annapolis Carr-Saffield Post of the 115th Infantry.

And of all the mothers who listened to their sons that day, only the organist is alive in 1958, Mrs. Brice Worthington, serene in her memories of a full life, lives alone in gracious old age as 12 Maryland Avenue.

[1] The new rector mentioned here is Rev. William R. Agate.

Reflection: “And the Waters Bore Up the Ark” - Genesis 7:17 as a Foreshadow of the Cross

By Fr. Wesley Walker

This Sunday’s Old Testament reading comes from Genesis 6.

Note: This was originally published at Conciliar Post.

“The flood continued forty days on the earth; and the waters increased, and bore up the ark, and it rose high above the earth.”

-Genesis 7:17 (NRSV)

Recently, I had occasion to complain to a friend about the elasticity of the word “literal” when wielded in discussions concerning hermeneutics. The word is frequently used as a placeholder for vapid personal interpretations derived in absentia of authorial intent, historical context, and the traditions of the Church. Medieval biblical exegete Nicholas of Lyra (1270-1349) argued for the duplex sensus literalis (“double-literal sense”) of the Bible. This view allows readers of Scripture to engage the text on the literal-historical level while also allowing for engagement on a prophetic level that makes room for a typological reading which sees the real, historical events recorded in Scripture as pointing to a grander, ultimate Reality (see Levy, Introducing Medieval Biblical Interpretation: The Senses of Scripture in Premodern Exegesis, 281-5). This helpful hermeneutic can guide us to encounter Scripture in a deeper, more canonical way. One fascinating example of the duplex sensus literalis is Genesis 7:17.

Genesis 7:17 details the great flood and the ark being lifted up by the waters. On a literal-historical level (however you might apply that term to what occurs in Genesis 1-11), this describes the magnitude of the flood, emphasizing the height of the ark above the earth because of the destructive waters. The Greek verb for “bore up” in the LXX is ύψοω (hypsoo). This is the same Greek word used in John 3:14-15, “And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life” and John 12:32, “And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all people to myself.” (emphasis added).

From the beginning, Christians have seen parallels between Noah’s Ark and Christ. 1 Peter 3:18b-21 uses the Ark as a parallel to Christ’s work and the sacrament of Baptism:

“He was put to death in the flesh, but made alive in the spirit, in which also he went and made a proclamation to the spirits in prison, who in former times did not obey, when God waited patiently in the days of Noah, during the building of the ark, in which a few, that is, eight persons, were saved through water. And baptism, which this prefigured, now saves you—not as a removal of dirt from the body, but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ.”

Christians took this to heart; it even influenced the architecture of churches. The central part of the church building became known as the nave which is a derivative of navis, a Latin word meaning “boat.” They did this because they understood that the Church, the institution established by Christ, to be an Ark which was keeping them safe from the destruction of sin in the outside world.

Augustine advanced his interpretation of Noah and the flood still further, even making use of the dimensions of the structure of the Ark as recorded in Scripture (Contra Faustum, XII, 14):

“Noah, with his family is saved by water and wood, as the family of Christ is saved by baptism, as representing the suffering of the cross. That this ark is made of beams formed in a square, as the Church is constructed of saints prepared unto every good work: for a square stands firm on any side. That the length is six times the breadth, and ten times the height, like a human body, to show that Christ appeared in a human body. That the breadth reaches to fifty cubits; as the apostle says, ‘Our heart is enlarged,’ (2 Cor 6:11) that is, with spiritual love, of which he says again, ‘The love of God is shed abroad in our heart by the Holy Ghost, which is given unto us’ (Rom 5:5). For in the fiftieth day after His resurrection, Christ sent His Holy Spirit to enlarge the hearts of His disciples. That it is three hundred cubits long, to make up six times fifty; as there are six periods in the history of the world during which Christ has never ceased to be preached — in five foretold by the prophets, and in the sixth proclaimed in the gospel. That it is thirty cubits high, a tenth part of the length; because Christ is our height, who in his thirtieth year gave His sanction to the doctrine of the gospel, by declaring that He came not to destroy the law, but to fulfil it. Now the ten commandments are to be the heart of the law; and so the length of the ark is ten times thirty. Noah himself, too, was the tenth from Adam. That the beams of the ark are fastened within and without with pitch, to signify by compact union the forbearance of love, which keeps the brotherly connection from being impaired, and the bond of peace from being broken by the offenses which try the Church either from without or from within. For pitch is a glutinous substance, of great energy and force, to represent the ardor of love which, with great power of endurance, bears all things in the maintenance of spiritual communion.”

In light of these connections, Genesis 7:17’s parallels with John 3:14-15 and 12:32 are all the more interesting. The Ark anticipates the lifting up of Christ on the cross.

What is the significance of the connection between the Ark and the crucifixion of Christ? St. Athanasius’ book On the Incarnation is helpful in answering this question. Explaining why Christ died the exact way he did, Athanasius makes some wonderful points about symbolism. He explains that Christ died the way he did because he had to be killed by enemies in public with witnesses (53-4). According to Athanasius, he was specifically crucified for two reasons. First, in crucifixion his arms were outstretched “that He might draw His ancient people with the one and the Gentiles with the other” (55). The other reason, which he connects to John 12:32, is that Christ had to be lifted up because: “the air is the sphere of the devil, the enemy of our race.” The devil, fallen from heaven:

“Endeavours with the other evil spirits who shared in his disobedience both to keep souls from the truth and to hinder the progress of those who are trying to follow it…the Lord came to overthrew the devil and to purify the air and to make ‘a way’ for us up to heaven, as the apostle says, ‘through the veil, that is to say, His flesh.’ He cleansed the air from all the evil influences of the enemy.” (55)

The cross is a symbol of Christus victor because, even in his death, Christ purges the air (Eph 2:2) from Satan’s influence, ultimately causing the defeat of Sin and Death.

Understanding the duplex sensus literalis can aid readers of Scripture in seeing the patterns and rhythms of God on display, as he continuously intervenes in time and space. Nothing in Scripture is there by accident. The Bible is not a haphazardly compiled collection. Much like an artist uses similar strokes, colors, subjects, lighting, etc. in their work, so God used and continues to use discernible types and figures to bring about the salvation of all things (2 Cor 5:19). As we encounter these types, we can expect them to point to Christ (Col 2:17). The Ark is no exception. Noah and his family were saved by being on the inside of the Ark as the flood waters purged the earth of life. Likewise, those who find themselves in Christ will be saved from their sins. In both the lifting up of the Ark and the lifting up of the Son of Man, God is glorified because of his salvific actions on behalf of his Creation.

Old Time Bible Hour: This Tuesday at 7p

The Old Time Bible Hour is a monthly study where we explore how Christians who have gone before us read the Scriptures. This month, we will be reading and discussing Hugh of Saint Victor’s interpretation of Isaiah 6 and Noah’s Ark.

Evening Prayer will be said at 6:30p.

You can download the reading here or email Fr. Wesley at wwalker@stpaulscrownsville.com.

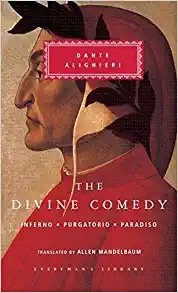

Fall 23-Spring 24 Friday Study: The Divine Comedy

The Divine Comedy is one of the most magnificent epic poems in the canon of Western Literature. In it, Dante Alighieri will take us on a journey set in the realms of the afterlife that serve as a backdrop to explore the human condition, theology, and beatitude. The Divine Comedy is divided into three parts, Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso. We will delve into the depths of Hell with Dante and his guide, Virgil; we will climb Mount Purgatory with them; and we will explore the glorious realms of heaven. Dante’s writing, which makes heavy use of symbolism, allegory, and moral teaching, will make us confront important realities like sin, justice, and divine mercy. This is a truly timeless work that still captivates and inspires many with its profound insights into the human soul and the eternal pursuit of truth and salvation. The study will range from August 25-May 3.

Bibliography of Recommended Resources

Recommended Translation: Dante. The Divine Comedy: Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso. Everyman’s Library 183. Translated by Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995. ISBN: 978-09-679-43313-2.

100 Days of Dante by Baylor University. https://100daysofdante.com/

Baxter, Jason M. A Beginner’s Guide to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2018. ISBN: 978-0801098734.

Leithart, Peter J. Ascent to Love: A Guide to Dante’s Divine Comedy. Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2001. ISBN: 978-1885767165.

Summer Study: The Genesis of Gender by Abigail Favale

Join us this summer for an engaging and thought-provoking study! We will be diving into Abigail Favale's insightful book, The Genesis of Gender: A Christian Theory, exploring the theological understanding of gender through a Christian lens. This study will provide a platform for meaningful discussions and reflections on this important topic.

We invite you to join us every Thursday for an enriching evening. We will begin with Evening Prayer at 5:00 PM, followed by a delightful dinner together at 5:30 PM. Afterward, from 6:15p to 7:15p, we will gather for our book discussion, delving into the profound themes presented in The Genesis of Gender.

Additionally, we are excited to offer educational activities for children during the study, providing an opportunity for them to grow in faith alongside us. It's a wonderful chance for families to come together and learn in a supportive community environment.

Mark your calendars for the first session on June 1 and subsequent sessions every Thursday until August 10. We encourage you to acquire a copy of the book in advance and read along to fully engage in the discussions. However, participation is not limited to those who have read the book—everyone is welcome! See you there!

For more information, please contact Fr. Wesley.

Reflection: Doubt Your Doubt

In his most recent sermon, Dcn. David reminded us that the First Sunday after Easter has often been called the Sunday of Thomas or Doubting Thomas Sunday. Historically, the Gospel lesson included the story of his doubting the resurrection and Jesus restoring his faith by showing him his wounds. This has got me thinking about the topic of doubt and how it’s important for all of us to doubt our doubt.

Doubt is, to some extent, built into our nature. Many people find themselves going through crises of faith at different points in their lives. Some doubts are more intellectual in nature, a failure to connect faith and reason well. Still, others doubt in a raw and emotional way.

In my own experience, nothing makes me doubt my faith more than the suffering of children. It’s so visceral for me that I can’t even formulate it in a rational way, other than to look at the situation and then look up and ask God, “How is this happening?” On an intellectual level, I can express an argument for why suffering exists, why Christianity best explains it, and why we look to the future when God will right these wrongs. Even then, my heart tends to be slow in coming around.

All this is to say: doubting is inevitable and the Church should never “doubt shame” someone into belief. Instead, the Church should be a place where one can ask authentic questions within a community that walks beside them through whatever issue they’re wrestling with.

At the same time, doubt should be done responsibly with a proper posture. That posture looks less like Job and more like Habakkuk. In Job, the title character uses a theological system known as retribution theology as a way to insist that God had made some kind of error and that his suffering was unjust. Still, the problem with Job seems less to do with his theology and more to do with the way he accuses God. Indeed, the oft quoted, “For I know that my Redeemer lives” (Job 19:25; RSV) is a defiant stand on his own self-righteousness and a complaint that he has to look elsewhere to be vindicated because God is in error.

In the book of Habakkuk, the prophet sees injustice in the geopolitical circumstances of the world. Israel, God’s covenantal people, are being bullied by other, stronger nations. The prophet hears God pronounce this as a judgment against Israel and can’t believe his ears. He argues against God’s plan but then, at the end of his protest, he says:

“I will take my stand to watch, and station myself on the tower, and look forth to see what he will say to me, and what I will answer concerning my complaint.” (Habakkuk 2:1)

Habakkuk is a model for doubting for those of us within the Church. He is honest with God while at the same time raising legitimate questions due to his lack of understanding.

All this is a preface to point out that there is a fad of contemporary Christians who rely heavily on the experience of doubt in ways that cause them to seriously deviate from (little-o) orthodoxy into a progressive Post-Evangelicalism.

Unfortunately, these instances of doubt can be more harmful than positive. It is possible to commodify one’s doubt, to brand oneself as “enlightened” at the expense of orthodox teaching, doctrine, and practice while still claiming to be Christian. In these situations, doubt allows doctrine to become fluid and subjective. Tradition becomes just merely a path where one “walks into the mystery of God” but there is no way to measure the validity of said traditions.

One of the implications of this mode of questioning is that the doubter can easily become the provocateur. Often times this can be out of a desire to be “prophetic.” It should be remembered, however, that doubt isn’t an excuse to obfuscate or confuse through vague, obnoxious, or cynical comments. It all goes back to posture.

Which brings us to the point. As Presbyterian Pastor Timothy Keller would say, “doubt your doubt!” That’s not an empty platitude. It’s an exhortation to radically interrogate the source of your doubt. Frequently, doubt can become a means by which we either intentionally or subconsciously distract from our own shortcomings and allow them to perpetuate. Sometimes are doubts can show us larger problems with ourselves than with our belief system.

But in instances where we do have legitimate doubts, let us remember the posture of Habakkuk and ultimately be willing to submit to God’s answer to our problem. Wielding doubt responsibly can help us further conform to the image of Christ and work through the tough issues. When it’s done irresponsibly, it can take us places we don’t want to go.

The 2023-2024 Intercommunion Prayer Cycle

As Anglicans, we believe strongly in the power of prayer. In particular, we believe in praying for Christ’s Church. Each year, we publish a Prayer Cycle where we pray for parishes and clergy in the jurisdictions with which we are in communion. You can find the Prayer Cycle below:

Reflection: The Paschal Triduum

The Paschal Triduum, also referred to as the Triduum Sacrum (Latin for “Three Holy Days), is the three day observation of Jesus’ Passion and Crucifixion. The Triduum includes Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday and ends at Evening Prayer on Holy Saturday when the Easter Celebration begins. These three ancient observations walk us through the tragically beautiful events that brought about our redemption. And so the purpose of this reflection is to make us more familiar with each day.

While these are three different days, they share the same basic subject: the Paschal Mystery. The Paschal Mystery refers to the Passion, Death, and Resurrection of Jesus Christ, the center of our faith. The term “paschal” connects these events to the Jewish Passover because Jesus is the fulfillment of God’s liberating activities in Exodus. Further, the Paschal Mystery is a cycle of death and new life as we walk with Jesus to the Cross and celebrate his glorious Resurrection. This macro-redemptive story reminds us of our own individual stories and how those of us who are “in Christ” have experienced those same cycles through the sacrament of Baptism in which we died to sin and were raised to walk in the newness of life.

The Triduum begins on Maundy Thursday. While the most “normal” of the services, there are still a few unique emphases and practices. First, we commemorate the Last Supper between Jesus and his friends as well as the institution of the Sacrament of the Altar: “Do this in remembrance of me.” Further, the Gospel reading is often the story of Jesus washing his disciples feet, reminding us of the great humility of our Savior and the mandatum (command) he gave to his followers (St. John 13:14-15): “If I then, your Lord and Master, have washed your feet; ye also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have given you an example, that ye should do as I have done to you.” At the end of the service, the Sacrament is moved from the Tabernacle over the Altar to an Altar of Repose and the Altar is stripped as we think about Jesus’ betrayal at the hands of one of his friends. No Mass is said from the end of the service until the Easter Vigil and the people leave this service in silence.

On Good Friday, the focus is on the Crucifixion of Jesus, the great sacrifice that the Paschal Lamb makes for us. Without the Cross, there is no Christianity as Jesus atones for our sins, enabling us to have a restored relationship with the Father. While Holy Communion is not consecrated on Good Friday, we do plenty to commemorate what Jesus did for us. At the beginning of a series of Scriptural passages are read: Hosea 5:15-6:6, Hebrews 10:1ff., and St. John 19:1ff. These passages and the prayers that attend them remind us of what Jesus accomplished for us. After that, we pray “The Solemn Collects,” prayers for the Church of God. The Solemn Collects mirror the Prayer for the Whole State of Christ’s Church as we pray for the Church to continue to spread the Gospel, our Bishop, Clergy and other servers, the President, catechumens, true doctrine, those who travel, those who have separated themselves from the Church through heresy and schism, preservation from the devil, and the conversion of the Jews and other non-Christians. Then we venerate the Cross, the precious instrument of our redemption. After we celebrate this symbol, we listen to the reproaches, those are verses from Scripture that are read reminding us of what God has done for us while we ask him for his mercy. Finally, we receive Communion from the Altar of Repose before leaving.

The Easter Vigil is the first celebration of Easter. The church is dark and we begin outside as we light a new fire. Once the fire is blessed, the Deacon uses it to light the Paschal Candle. He then leads a processional into the church chanting, “The light of Christ” while the people respond “Thanks be to God.” The Paschal Candle is used to light all the candles on the Altar. This reminds us that Christ is the light of the world who shines in the darkness (St. John 1:5). When the candles have been lit, we sit for the reading of prophecies that anticipate the Resurrection of Jesus. Then the Baptismal Font is blessed. Just as Jesus was laid to rest in the Tomb only to burst forth after his Resurrection, so the Font is both a tomb and a womb for us. In it, the old person dies and the new is raised to life. When the Font has been blessed, the priest then changes from purple into white and the Easter celebration begins as we go to the Altar and receive Holy Communion!

These three sacred days are about observing the events at the heart of our faith. Yet the goal is not to treat them as purely liturgical events. Liturgy is important because it forms and shapes us; it cultivates our imaginations and trains us to take the Gospel into the world. We vividly recollect Our Lord’s Passion, Death, and Resurrection so that we might be a people who live out the rhythm of the Paschal Mystery in our own lives.

Reflection: The Palm Sunday Processional

Palm Sunday is the beginning of Holy Week. I’ve always found it to be a strange way to begin Holy Week because of the way the crowds celebrate Jesus’ arrival despite the fact that he was dead less than a week later. Still, the point of the liturgical observations of Holy Week is to walk with Our Lord through the story: we enter Jerusalem with him, we sup with him and the disciples at the Last Supper, we strip the altar as we reflect on Judas’ betrayal, we reflect on the horridness of the Crucifixion, while also venerating the Cross as a beautiful symbol of our redemption. At the Easter Vigil, we anticipate the resurrection through the reading of Old Testament prophecies and the blessing of the baptismal font where new Christians will be birthed. Finally, on Easter morning, we celebrate the fact that “He is not here; for he is risen.”

The Palm Sunday Processional, as it’s currently practiced, goes all the way back to at least the fourth century. The first record of it that we have is in the diary of a Spanish pilgrim to Jerusalem who noted that the Christian inhabitants of the city would process into the city with palms while singing hymns. I take this to mean the tradition had been established for some time prior to this record. We know the tradition spread until it was made a virtually universal liturgical practice by the fifth century. As Western Christians, we receive it from the liturgical work of Gregory the Great who made it a normal practice while he was Bishop of Rome (440-461).

Biblically, the Palm Sunday Processional can be traced back to all four of the Gospels, which all describe Jesus riding into Jerusalem on a donkey while the people lay palm branches on the ground and shouted "Hosanna!" This event fulfilled the prophecy in Zechariah 9:9, part of Sunday’s Old Testament reading, which states, “Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion; shout, O daughter of Jerusalem: behold, thy King cometh unto thee: he is just, and having salvation; lowly, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt the foal of an ass.”

The Palm Sunday Processional is significant for several reasons. As mentioned above, it marks the beginning of Holy Week, a time of deep reflection and penance for Christians around the world. Secondly, it symbolizes Jesus' arrival as the long-awaited Messiah, the fulfillment of God's promise to send a savior to the world. Thirdly, it represents the paradox of Jesus' kingship, as he entered Jerusalem not on a magnificent horse, but on a humble donkey. It reminds us that, unlike most earthly kings, Jesus does not win his victory through great military strength, impressive political machinations, or charismatic personality—quite the opposite! Jesus wins his victory through his suffering and death on the Cross, reminding us of St. Paul’s words in I Corinthians 1:23-24, “We preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumblingblock, and unto the Greeks foolishness; But unto them which are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God, and the wisdom of God.”

The Palm Sunday Processional is an opportunity for us to reflect on our lives. In what areas of our lives do we need to open our arms and receive him who “comes in the name of the Lord”? How have we been like the Pharisees and religious leaders who opposed Jesus?

Palm Sunday is an old tradition. As we process, I encourage you to consider the fact that Christians like you have been doing this for over 1,500 years. But more importantly, use the Processional as an opportunity to remember Jesus’ sacrifice and love for us so that we can approach Holy Week with open hearts and minds, ready to deepen our relationship with God as we commemorate the cosmos-changing events that took place 2,000 years ago.

“All glory, laud, and honor

to you, Redeemer, King,

to whom the lips of children

made sweet hosannas ring.

You are the King of Israel

and David's royal Son,

now in the Lord's name coming,

the King and Blessed One.

The company of angels

is praising you on high;

and we with all creation

in chorus make reply.

The people of the Hebrews

with palms before you went;

our praise and prayer and anthems

before you we present.

To you before your passion

they sang their hymns of praise;

to you, now high exalted,

our melody we raise.

As you received their praises,

accept the prayers we bring,

for you delight in goodness,

O good and gracious King!”