Confession: Hearing God's Story about Ourselves

This is Part 3 of a series based on our recent retreat “Forgiving Ourselves.” Part 1 can be found here. Part 2 can be found here.

As humans, we think in terms of stories. Beginning, conflict, and end. When we want to get to know someone, we might invite them to tell us their story. Stories are key to understanding the world and our place in it. The great myths in ancient cultures were attempts to understand the world. We tell stories about our experiences and relationships so that we can understand them better. The Christian religion tells us a story, the most meaningful story of all. We might call this a meta-story, the story in which all other stories fit. It has three acts: Creation, Fall, and Redemption. Creation, the opening act, means God made the world and everything in it is good. The Fall, the conflict, means that our sin not only hurt ourselves but subjected the whole cosmos to the futile effects of sin. But the resolution of the Christian story is the most beautiful act of all: redemption. Jesus Christ has come to redeem us and will come again to deliver us once and for all. Everything will be made right. Each of us can understand our own stories—our struggles, failures, victories, relationships, and everything else—in terms of the meta-story of the Gospel. And so when we talk about the Sacrament of Reconciliation, we should understand it as telling us a story about ourselves.

Real life, of course, is often more complicated than the stories we want to tell ourselves about ourselves. We like to think of ourselves as the heroes, the protagonists of our stories. But, sometimes, we might have been the villain. As Christians who have been incorporated into Christ, we might tell the story of our testimony as the resolution of a conflict: I became a Christian because God gave me the grace to realize that I had enough of sin and realized I couldn’t do it anymore. However, it’s important to note that in our day-to-day lives as Christians, we experience a good deal of continuity and discontinuity with that story. That discontinuity we might call sin: when we don’t do what we’re supposed to or when we do what we’re not supposed to. This world and all our short comings is not God’s plan B. He knew that we would still struggle with temptations and sin after our baptisms, hence the great tension of Romans 7: I do what I don’t want to do; I don’t do what I want to do. Who will save me from this body of death? And so God gave us a way of re-storying ourselves: the sacrament of Confession. There are two ways we can enact this story, devotionally or sacramentally.

Devotional confession is that which we experience during the Holy Communion service, what we do during Morning and Evening Prayer, and the confessions we make directly to God in our personal prayers. As Psalm 51:17 states, “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and a contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise.” And so, when we begin our Offices or before we come to the Altar at Holy Communion, we pray a prayer of confession, we tell God the broken parts of our stories: “We acknowledge and bewail our manifold sins and wickedness, which we, from time to time, most grievously have committed, by thought, word, and deed against thy divine majesty.” We do this knowing that only God can take the “intolerable burden” of our sins from us. It’s important to note that the absolution given after devotional confessions is contingent on the perfect contrition of the people: “Almighty God, our heavenly Father, who of his great mercy hath promised forgiveness of sins to all those who with hearty repentance and true faith turn unto him; Have mercy upon you; pardon and deliver you from all your sins; confirm and strengthen you in all goodness; and bring you to everlasting life; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen” (emphasis added). Imperfect contrition is when we confess our sins because we’re scared of being punished or going to Hell. Imperfect contrition is when we think about absolution like fire insurance. Perfect contrition, on the other hand, occurs when we are sorry for our sins because we know that we have wronged God. Either way, it is important for us to engage in these regular corporate acts of confession because they ground us in a rhythm of life that brings us to an awareness that we are not what we should be and places our faith in what God is capable of.

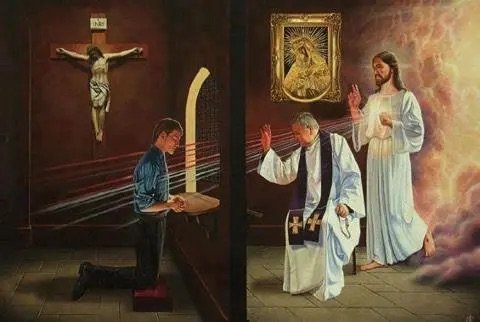

The devotional confessions we make are not, properly speaking, the Sacrament of Reconciliation. This is because Sacraments provide assurance: Baptism is what Jesus says it is in that it brings someone into a covenantal and personal relationship with God; the Eucharist is what Jesus says it is, his Body and Blood, whether we believe that it is or not. Because the Confessions at Morning/Evening Prayer and Holy Communion are contingent, it may be that there are times where you, or others, are not sure if you’ve been absolved because you are not sure whether your contrition was perfect or imperfect. For this reason, God has given us the Sacrament of Reconciliation which finds its roots in the beautiful story of the Johannine Pentecost when Jesus appears to his disciples in the locked room, breathes on them and says, “Receive ye the Holy Ghost: Whose soever sins ye remit, they are remitted unto them; and whose soever sins ye retain, they are retained.” These verses are read over the Priest at his ordination because the Christian Priest participates in the High Priesthood of Christ. In other words, when you come to Confession and the priest says, “I absolve you of all your sins in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,” no more hand-wringing is needed; you have been absolved. Your story has been re-written in real time.

The stories we tell ourselves about ourselves matter. It’s possible that we tell ourselves an autobiography that is skewed and self-destructive. The Gospel, the meta-story, is big enough to incorporate and redeem the many twists and turns that might appear in our stories. In Confession and Absolution, we hear God’s version of our stories told authoritatively. “Self-forgiveness” begins here: not with our laxity or scrupulosity, but with God’s Word. The question is whether we believe him or not.