NEWS

Confession: Hearing God's Story about Ourselves

This is Part 3 of a series based on our recent retreat “Forgiving Ourselves.” Part 1 can be found here. Part 2 can be found here.

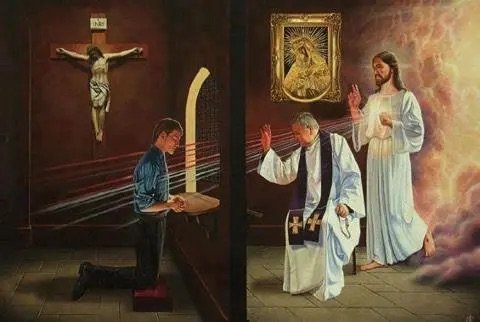

As humans, we think in terms of stories. Beginning, conflict, and end. When we want to get to know someone, we might invite them to tell us their story. Stories are key to understanding the world and our place in it. The great myths in ancient cultures were attempts to understand the world. We tell stories about our experiences and relationships so that we can understand them better. The Christian religion tells us a story, the most meaningful story of all. We might call this a meta-story, the story in which all other stories fit. It has three acts: Creation, Fall, and Redemption. Creation, the opening act, means God made the world and everything in it is good. The Fall, the conflict, means that our sin not only hurt ourselves but subjected the whole cosmos to the futile effects of sin. But the resolution of the Christian story is the most beautiful act of all: redemption. Jesus Christ has come to redeem us and will come again to deliver us once and for all. Everything will be made right. Each of us can understand our own stories—our struggles, failures, victories, relationships, and everything else—in terms of the meta-story of the Gospel. And so when we talk about the Sacrament of Reconciliation, we should understand it as telling us a story about ourselves.

Real life, of course, is often more complicated than the stories we want to tell ourselves about ourselves. We like to think of ourselves as the heroes, the protagonists of our stories. But, sometimes, we might have been the villain. As Christians who have been incorporated into Christ, we might tell the story of our testimony as the resolution of a conflict: I became a Christian because God gave me the grace to realize that I had enough of sin and realized I couldn’t do it anymore. However, it’s important to note that in our day-to-day lives as Christians, we experience a good deal of continuity and discontinuity with that story. That discontinuity we might call sin: when we don’t do what we’re supposed to or when we do what we’re not supposed to. This world and all our short comings is not God’s plan B. He knew that we would still struggle with temptations and sin after our baptisms, hence the great tension of Romans 7: I do what I don’t want to do; I don’t do what I want to do. Who will save me from this body of death? And so God gave us a way of re-storying ourselves: the sacrament of Confession. There are two ways we can enact this story, devotionally or sacramentally.

Devotional confession is that which we experience during the Holy Communion service, what we do during Morning and Evening Prayer, and the confessions we make directly to God in our personal prayers. As Psalm 51:17 states, “The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit: a broken and a contrite heart, O God, thou wilt not despise.” And so, when we begin our Offices or before we come to the Altar at Holy Communion, we pray a prayer of confession, we tell God the broken parts of our stories: “We acknowledge and bewail our manifold sins and wickedness, which we, from time to time, most grievously have committed, by thought, word, and deed against thy divine majesty.” We do this knowing that only God can take the “intolerable burden” of our sins from us. It’s important to note that the absolution given after devotional confessions is contingent on the perfect contrition of the people: “Almighty God, our heavenly Father, who of his great mercy hath promised forgiveness of sins to all those who with hearty repentance and true faith turn unto him; Have mercy upon you; pardon and deliver you from all your sins; confirm and strengthen you in all goodness; and bring you to everlasting life; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen” (emphasis added). Imperfect contrition is when we confess our sins because we’re scared of being punished or going to Hell. Imperfect contrition is when we think about absolution like fire insurance. Perfect contrition, on the other hand, occurs when we are sorry for our sins because we know that we have wronged God. Either way, it is important for us to engage in these regular corporate acts of confession because they ground us in a rhythm of life that brings us to an awareness that we are not what we should be and places our faith in what God is capable of.

The devotional confessions we make are not, properly speaking, the Sacrament of Reconciliation. This is because Sacraments provide assurance: Baptism is what Jesus says it is in that it brings someone into a covenantal and personal relationship with God; the Eucharist is what Jesus says it is, his Body and Blood, whether we believe that it is or not. Because the Confessions at Morning/Evening Prayer and Holy Communion are contingent, it may be that there are times where you, or others, are not sure if you’ve been absolved because you are not sure whether your contrition was perfect or imperfect. For this reason, God has given us the Sacrament of Reconciliation which finds its roots in the beautiful story of the Johannine Pentecost when Jesus appears to his disciples in the locked room, breathes on them and says, “Receive ye the Holy Ghost: Whose soever sins ye remit, they are remitted unto them; and whose soever sins ye retain, they are retained.” These verses are read over the Priest at his ordination because the Christian Priest participates in the High Priesthood of Christ. In other words, when you come to Confession and the priest says, “I absolve you of all your sins in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost,” no more hand-wringing is needed; you have been absolved. Your story has been re-written in real time.

The stories we tell ourselves about ourselves matter. It’s possible that we tell ourselves an autobiography that is skewed and self-destructive. The Gospel, the meta-story, is big enough to incorporate and redeem the many twists and turns that might appear in our stories. In Confession and Absolution, we hear God’s version of our stories told authoritatively. “Self-forgiveness” begins here: not with our laxity or scrupulosity, but with God’s Word. The question is whether we believe him or not.

Reflection: Our Identity in God

This is Part 2 of a series based on our recent retreat “Forgiving Ourselves.” Part 1 can be found here.

In our modern world, we view the individual as a collection of identities: Race, class, sex, sexual orientation, vocation, and a whole host of other factors. But as Christians, we don’t believe that “Christian” is simply another adjective alongside the host of other facets of our identities. We believe that “Christian” is the organizing principle of our lives that impacts every part of who we are. You’re not a Christian who is a parent…you’re a Christian parent. In other words, the fact that you’re a Christian impacts you at every level—including how you parent. By describing ourselves as Christians, we aren’t just identifying ourselves with the person of Jesus Christ; we’re identifying ourselves with the entire Godhead. It’s through Jesus that we’re saved, but we’re saved to become partakers of the divine nature (2 Pet 1:4). If that’s true of us—that we are partakers of the divine nature—then who we are isn’t just determined by our families, how and where we were raised, what we studied in school, the jobs we work, or anything else…the most important fact about us is that we are “in Christ” and, therefore, participants in the life of the Trinity.

We can locate our identity in the Father.

God the Father is existence itself. We exist because of the Father. “In him, we live, and move, and have our being” (Acts 17:28). This means that everyone who exists, by virtue of their existence, has a relationship with the Father. Because God didn’t have to make the world or anything in it, but chose to create anyways, we know that he is good and that he loves us. Life is a gift constantly reminding us of his presence. This also means that human nature is good; in our current state, it’s been twisted and perverted by sin but, at its core, it is a creation that God made and said “it is good.”

We can locate our identity in the Son.

The Second Person of the Trinity, the Word, is the Wisdom of God and the Redeemer. The Word is the underlying logic of creation; the fact that we are created in his Image means that we have the ability to reason. But it’s also important that we remember that “the Word became flesh.” Sin means we couldn’t find our way back to God after we sinned; Jesus’ life, death and resurrection are offered to the Father for us. When we are baptized, then, we are immersed into Christ: we receive the remission of our sins, the gift of the Holy Spirit, and adoption as children of God.

We can locate our identity in the Holy Spirit

The Holy Spirit is God’s gift to the baptized. Unlike existence and rationality, this gift isn’t given to everyone necessarily. According to the Church Father Origin, we receive the Holy Spirit “that we should be holy—we become capable of Christ anew in respect of his being the Righteousness of God.” This reminds me of a prayer the Priest prays as he mingles the water and wine during the preparation for Holy Communion: “By the mingling of this water and wine, may we come to share in the divinity of he who humbled himself to share our humanity.” The Holy Ghost, then, is the Person of the Trinity who brings us further up and further in to lives of holiness. It’s important to remember that holiness has both inward-facing and outward-facing features to it. Inwardly, we are called to be pure, unspotted by the world. But that purity is always externally directed, it’s about attracting others to God. And so the Holy Spirit leads us, prompts us, and draws us further into the life of God so that we can live holy lives. He does this by the Eucharist, as we pray during the Canon, “vouchsafe to bless and sanctify, with they Word AND HOLY SPIRIT, these thy gifts and creatures of bread and wine; that we, receiving them according to thy Son our Saviour Jesus Christ’s holy institution in remembrance of his death and passion, may be partakers of his most blessed Body and Blood.” He does this through prayer as the “Spirit of adoption, whereby we cry, Abba father” (Rom 8:15). Finally, the Holy Spirit does this through God’s dynamic ordering of the world, putting us in places that we need to be.

So who are you?

You are created by God. You are a divine Image bearer and you are unique: God created you to be you and no one else.

You are a rational creature who can think, speak, and participate in God’s Wisdom.

You are loved by God as a child, called to be holy and destined to spend eternity in communion with him.

Whatever else happens, we must let God’s story be the setting for our story.

"I Will Offer the Eucharist for You" by Lee Stevens

In Sunday’s sermon, Fr. Wesley mentioned that he and Fr. David pray for each member of St. Paul’s at least once a week at the intentions of Holy Communion. The tract,“I will Offer the Eucharist for You,” explains what that means. It was originally written by Lee Stevens, a member of the Order of the Holy Cross. The text is as follows:

Recently, a very earnest and much puzzled young Church woman said to me, “Father, what is all this business of offering the Holy Eucharist ‘with special intention’ for persons and things? Can’t we offer at least our Eucharistic worship without spoiling it by begging God for something through it? We do plenty of begging in our private prayers, and it seems to me that’s the place for it. Please explain.”

Because there may be many others to whom this idea of offering the Eucharist with special intention is new or strange, let’s investigate the meaning of it.

The Holy Eucharist is like a great jewel having many facets, each sparkling and glowing with its own special wonder and brilliance. It is first of all an act of praise, adoration, worship…the most perfect we can offer to God because it is our Lord’s own act and He lets us share in it. It is, again, the supreme act of thanksgiving to Almighty God for Himself and for all His blessings bestowed upon us and all men. (The word “Eucharist” comes from the Greek and means thanksgiving.) And yet again, the Eucharist is our great God-given means of communion and union with Himself: we are fed with the Divine Life when we receive Christ’s precious Body and Blood in our Communions, and are made one with Him. But the wonderful glowing heart of the jewel lies here: It is the Great Sacrifice of our Lord offered on the Cross for the salvation of the whole world! A little deeper consideration of this sacrificial aspect of the Eucharist will bring out the answer to our friend’s question.

On the Cross of Calvary that first Good Friday Jesus offered Himself to God the Father to be the full, perfect, and sufficient Sacrifice, Oblation, and Satisfaction for the sins of the whole world. That Sacrifice was made once and for all on that Cross. As our Great High Priest in heaven, Jesus is continually offering, pleading that Sacrifice before the Father for us all. It is the work of His sacred Humanity now, there at the right hand of the Father.

On the night before He died, Jesus left us a wonderful way in which we can share in His offering of His Sacrifice to the Father, a way in which we can participate in His Great work of salvation. He gathered His Apostles together for a Last Supper. At that meal He instituted the Great Sacrament we call the Holy Eucharist. He said to them, “DO THIS.” They began immediately after Pentecost to “do this,” and the Church has continued to “do this” as its chief act of worship ever since. We “do this” at ever Eucharist we offer.

At each Celebration we offer again to the Father the Sacrifice Christ offered on the Cross. What Jesus did at Calvary we re-present to God the Father. We offer again and again the Great Victim, His Body broken and Blood outpoured for the world…though no longer as a bloody sacrifice. (Jesus is not destroyed again in the Eucharist.) It is now a sacrificial memorial of the precious body and Blood offered to the Father…that Sacrifice so freely given on Calvary by the saving Christ. Jesus is continually offering It to His Father in Heaven. In the Eucharist we on earth have our share in what is going on in Heaven.

Jesus offered and continues to offer His Sacrifice of Himself for one purpose: the salvation of the whole world, and of every individual human soul. The merits He won for mankind on Calvary are limitless. He has won for us far more grace than will ever be needed for the salvation of every soul who has ever lived or ever shall live. All grace flows from His Cross. We, in our turn, offer His Great Sacrifice in every Eucharist for the salvation of the whole world and of every individual human soul. And it is our wonderful privilege to offer It with special intention for any particular soul whose special need is known to us. In doing so, we are asking that the merits won by Christ on Calvary, as they are to be bestowed through this particular Eucharist, may be applied to that soul; that the special graces needed by that soul may be supplied to it by our Lord. For example, we offer the Great Sacrifice with special intention for Aunt Sarah for comfort in her bereavement; for William in critical illness; for conversion for Everett; for Charles who is being ordained Priest today; etc. We may offer It also for special things, events, activities, etc., as when we offer the Eucharist for God’s blessing upon the life and work of the Order of the Holy Cross; for the peace of the world; for the Missions of the Church. We may offer It for the repose of the souls of the faithful departed; ordinarily this is done through a Requiem, although one may offer any Eucharist with this intention.

It is not clear from the foregoing, then, that the greatest possible act of love you can perform for any person is to offer the Great Sacrifice of the Eucharist with special intention for that person in his need? You are pleading Christ’s perfect Sacrifice in his behalf…the one perfect thing you can do on earth! Not until the last day will it be known to you how great the blessings you called down upon him…blessing he otherwise would not have had.

Now…a few practical helps. Set the intention with which you plan to offer the Eucharist on the night before as part of your regular preparation. Have one intention or as many as you wish. (My Bishop says the more the better!) Here is a simply prayer for directing your intention:

“O God, who makest the unworthy worthy, the unclean clean, and sinners to be holy, cleanse my heart and soul from all stain of sin, that I may worthily assist at Thy holy Altar; and grant that the Sacrifice to be here offered may be acceptable to Thee. I intend to offer It in union with Thy One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic Church:

As an Act of Adoration;

As a thanksgiving for all Thy mercies

As a sin-offering for all my sins and offenses;

As an Act of Supplication

for the salvation of all men,

for Thy whole Church,

for my family and friends,

for the faithful departed,

for all sick and suffering,

for the dying,

and especially for (here list your special intentions),

and for myself, that I may grow in vritue and obtain the rewards of Thy Kingdom. Amen.”

Make it a point to be in Church at least five minutes before the Service begins. Kneel down and say:

In the Name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost. Amen.

You regular prayers and Immediate preparation for this Eucharist.

Repeat the above prayer for directing your intention.

There are various ways of recalling your special intention during the Service. Do it any way most comfortable for you. You can renew it consciously at the Offertory. You can take it with you as you go up to the Altar Rail to receive (or have it in mind as you make your Spiritual Communion in your pew, if you are not receiving sacramentally at this Eucharist).

After the Celebration is over, as you linger to make your thanksgiving, make it a point to thank God for the wonderful blessings He has bestowed, unknown to you, upon those for whom you have just offered the Sacrifice.

Reflection: The Three Dimensions of Forgiveness and the Problem of Self-Forgiveness

During the events leading up to Jesus’ crucifixion, the Gospels give us two characters who fall but take radically different courses of action in response. The first is Judas who, in light of his betrayal of Jesus, spirals into self-destruction, unable to turn to God or the other Apostles for forgiveness. The second character presented by the Gospels is St. Peter who denies Jesus thrice after he was arrested. John 21:1-19 details the intimate scene in which Jesus restores Peter by asking three times, “lovest thou me more than these?” One of these characters was able to receive forgiveness from God; the other was not. St. Peter was restored to become one of the greatest preachers in history while Judas died in a nihilistic act of suicide.

Forgiveness is the event and or process of releasing someone from a debt, resentment, or grudge. Forgiveness can be, and often is, a struggle. It has three dimensions: the vertical, the horizontal, and reflexive.

The vertical dimension of forgiveness pertains to our relationship with God. Divine forgiveness is unidirectional: God forgives us when we sin. We cannot forgive God because he can’t sin. We see this one-direction of forgiveness at the very beginning when God kills an animal and covers Adam and Eve after their sin. This primeval sacrifice foreshadows not only the intricate Old Testament sacrificial system, but also the ultimate sacrifice of Christ on the Cross which pays the debt of sin we couldn’t pay. Jesus offered his perfect life and death to God the Father, earning infinite rewards, what the Book of Common Prayer, calls merits. But since Jesus is God, he has no need for these rewards and so he passes them on to those who are in Christ. We receive those merits through our baptismal reality. We believe in “one baptism for the remission of sins.” Baptism immerses us into the Christ story that brings about forgiveness for our sins. Without forgiveness, we could only experience God’s justice which, in our state of sin, would only ever bring death. Forgiveness from God is the foundation for all other kinds of forgiveness. Only God can begin the cycle of forgiveness, restoration, and healing.

The horizontal dimension of forgiveness involves at least two human parties, either individual or corporate. First, there is the party that is wronged, in perception or by action. And of course, one of the first tasks is to determine the nature of the wrong: did it actually happen or was it imagined; was it done on purpose or by accident? Then there is the guilty party, the person or group of people who committed the wrong. Forgiveness, in this context, means releasing the other person from a debt or grudge, whether they ask for it or not. For this reason, horizontal forgiveness is not the same thing as reconciliation. When one party sins against another, it drives the two apart. Forgiveness does not necessarily repair the gap between the two parties in an actual sense; reconciliation is a further process initiated by forgiveness in which both parties attempt to bridge the gap caused by the initial sin so that a relationship is restored.

The vertical and horizontal aspects of forgiveness are connected. Horizontal forgiveness is commanded of Christians because they have been forgiven in the vertical dimension. This is what St. Paul gets at in Ephesians 4:32, “Be ye kind one to another, tenderhearted, forgiving one another, even as God for Christ’s sake hath forgiven you.” The Lord’s Prayer makes it clear that the status of our vertical forgiveness can be affected by our capacity for horizontal forgiveness: “And forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.”

The third and final dimension of forgiveness is reflexive. When we sin, it’s possible that we judge ourselves more harshly than others do. Indeed, we may even judge ourselves harsher than God does. Because sin is finite and there are some sins worse than others, it’s possible that we deem what we did as worse than what it was. For all the damage and horror that sin can bring on others, it’s always worse to commit a wrong than to be wronged because sin warps us. Whatever violence we unleash on others, it’s always a more severe violence done to ourselves. In his autobiography, Frederick Douglass requires the inhumanity of various slave masters. The most tragic example was the wife of his master when he lived in Baltimore. Initially, she was kind of Frederick because she had never participated in the demonic slave trade before. She even taught him to read. But when her husband chastised her for treating Douglass humanely, she began acting cruelly towards Douglass so dramatically that he describes the change in her disposition from that of an angel to that of a demon. Forgiving ourselves isn’t so much about releasing our selves from a debt as being convinced of what has been said in the vertical and horizontal dimensions. Self-forgiveness is integrating ourselves around what God has already made true about ourselves.

Much of the modern literature about self-forgiveness is dangerous because the modern world doesn’t see or recognize the vertical component of forgiveness, which inevitably warps the horizontal and reflexive dimensions. One major problem with self-forgiveness is an authority issue: if I have wronged God and others, who am I to forgive myself, especially if I have not been forgiven by those I’ve wronged? A second problem with rhetoric around self-forgiveness is laxity. This occurs when we let ourselves off too easily. “Oh, it wasn’t that bad,” we may tell ourselves. This problem is related to an additional one which is scrupulosity, the vice of being too hard on ourselves. Ultimately, this isn’t just a sin against ourselves, but against God, because we are effectively saying his justice is insufficient. If we lack authority to forgive ourselves and are constantly risking laxity or scrupulosity, then we need a voice outside of ourselves to assure us that we are forgiven. This voice is the Word of God: “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing.”

In coming newsletter reflections, we are going to talk about our identity in Christ, the importance of confession, and the application of self-forgiveness.

Reflection Questions

Reflect on St. Matthew 27:1-10. How are each of the three dimensions of forgiveness neglected in this passage?

Think about a time you were forgiven. How did you feel? What were the results?

Think about a time you have forgiven someone else. How did you feel? What were the results?

Create a list of people you feel God is calling you to forgive. Remember, Jesus Christ has died on the cross for each person on your list. Commit to praying for the people on your list on a regular basis and, if you find yourself unable to forgive them, remember that Jesus has forgiven them.

Reflection: The Anglican Joint Synods 2023

In 2017, the Anglican Province of America, Anglican Church in America, and the Anglican Catholic Church signed an Intercommunion Concordat. This intercommunion agreement means that each of the participating churches recognize each other as valid, share clergy, and cooperate together towards the common end of “full, institutional, and organic union with each other, in a manner that respects tender consciences, builds consensus and harmony, and fulfills increasingly our Lord’s will that His Church be united” and “to seek unity with other Christians, including those who understand themselves to be Anglican, insofar as such unity is consistent with the essentials of Catholic faith, order, and moral teaching.” As a result of the Concordat, the three churches now gather together every three years for what is called a Joint Synod. At the Synod, we conducted the business of our own individual dioceses and provinces while also doing activities together—Morning and Evening Prayer, Mass, and various talks by bishops and clergy from across the Continuing Anglican Movement.

From a business perspective, synod went well with no major business conducted. We finalized the diocesan budget and heard many reports about parishes that are growing and flourishing. The Domestic Missions Board has done great work through the yearly Lenten Appeal to revitalize dormant parishes by bringing in new priests who can serve full time. The Board announced an additional focus on church planting to supplement this revitalization work moving forward. The diocese is growing and, with continued work, it will continue!

In his “State of the Church” Synod address, our Bishop, Chandler Holder Jones, cast a vision of what the APA can and should be. He emphasized that we are a missional church that needs to be about doing the work of spreading the Gospel. Assuming current trends continue, the Church in America will continue to lose people. No longer is it assumed that folks will attend a parish. In this inhospitable landscape, only healthy churches will survive. What does it mean to be a healthy church? Not programs, not political activism, not a country club aesthetic; a healthy church is one that is faithful to Scripture and Tradition and that makes disciples. Our current cultural moment, while apparently bleak, is an opportunity. The harvest is ripe!

In response to this challenge and opportunity, the Bishop laid out principles for action.

1) Our communion with our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ must be personal and real. Do we have a personal relationship with him?

2) Personal holiness is the greatest attractant for evangelization.

3) We need Bible-centered and Bible-saturated religion that understands Scripture as a way we encounter God.

4) We need Sacramental participation in all seven Sacraments—Baptism, Confirmation, Reconciliation, Unction, Holy Matrimony, Ordination, and Unction. These should be celebrated regularly and with all reverence and beauty.

5) Parishes must be active in Christian formation.

6) We have to be obedient to the Tradition of the Church and avoid private judgment, submitting ourselves to the Scriptures and the Primitive Church.

7) We need faithful discipleship that pushes us to deepening holiness that manifests itself in good works.

8) In addition to discipleship, we need to be evangelists. All Christians are called to preach Christ crucified.

9) We must maintain an unswerving commitment to the Anglican tradition as we have received it through the Affirmation of St. Louis.

These are wonderful exhortations from our shepherd and Bishop. The encouraging thing is that many of these points are already in practice at St. Paul’s. However, I would ask you to reflect on these points and pray that God would enable our parish to continue to be about our mission, and that wherever we are falling short, that God would give us the grace to grow!

Reflection: What We Talk About When We Talk About Holiness

Recently, I was visiting a parishioner in the hospital and he made a great point: sometimes, those of us who have been raised in the Church use certain words and we take them for granted without pausing to consider what they truly mean. Words like Glory, fellowship, and salvation are so pervasively used that we often lose sight of their meaning. I was reminded of this phenomenon this week at St. John’s College where we recently launched a book discussion group with some of our St. Paul’s students. We were discussing C.S. Lewis’ masterful book The Great Divorce and, in the course of the conversation, I threw out the term “grace.” Someone asked me to define that term and I balked, realizing that it denotes a much more complex idea than I was prepared to explain in the moment.

A common term we use a lot, and the one I want to focus on today, is holiness. We talk about God as holy and our desire to acquire holiness. But what does it mean to be holy?

Kadesh. Hagios. These are the Hebrew and Greek words most commonly used in the Bible for “holy.” In Latin, the term is sanctus from which we get our word sanctuary, a holy place set apart for the worship of God. Holiness refers to set apartness. When it comes to morality, this carries a sense of purity but it refers to more than that. Usually, when people are set apart, they are set apart for something.

After passing through the Red Sea, Moses and Israel sing, “Who is like unto thee, O Lord, among the gods? Who is like thee, glorious in holiness, fearful in praises, doing wonders?” In I Samuel 2:2, Hannah, the mother of Samuel, echoes her forefathers’ sentiments by praying, “There is none holy as the Lord: For there is none beside thee: Neither is there any rock like our God.” It’s God’s holiness that causes him to be worshipped in heaven in Isaiah 6:3: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord of hosts: The whole earth is full of his glory.” God is holy because no one else is like him. As our Creator, God is completely and utterly distinct from his creation. While us creatures can be good or bad, God is perfect; while we waiver between virtue and vice, he is constant. It’s not that God acts a certain way and proves that he’s holy; the opposite is true: God is holy and so his actions are holy.

In the Old Testament, one of the implications of God’s holiness is that the people of Israel, his Chosen People, were called to be holy. Because God is holy and Israel was to represent God to the world, they were called to be holy too. In Leviticus 19:2, God instructs Israel, “Ye shall be holy: for I the Lord your God am holy.” Israel’s holiness was always derivative of God’s holiness; they could become holy by participating in God’s life. How were they to do this? The answer is the Law of Moses which teaches us how to live in ways that are pleasing to God. Israel’s Law set them apart from their neighbors. They had to eat differently, live differently, and worship differently than the nations around them.

The New Testament calls the Church to an analogous holiness. In fact, the kind of holiness Christians are called to is more radical because it’s from the inside out. One of the problems with law in general is that it is behavior management. One can abide by the letter of the law and still miss the real purpose. The Christian law is interior. It’s not enough to not commit adultery because you shouldn’t even lust. It’s not enough to not murder because you shouldn’t even get angry at someone in your thought. This is a totalizing holiness that cuts to the heart of the person. That’s why St. Paul summarizes Christian ethics with a singular word: love. “He that loveth another hath fulfilled the law” (Rom 13:8). In a world characterized by violence and hatred, the love God shows us, and that we can then extend to others, sets us apart.

But what is holiness for? The answer has two parts that connect like a graph with vertical and horizontal axes. The first and primary reason for our holiness is the vertical dimension. It’s through holiness we worship God. “Present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God, which is your reasonable service” (Rom 12:1). In the Old Testament, an animal might be sacrificed to God as a picture of the coming redemption through Jesus Christ. Now that redemption is here, we respond not by killing an animal but by living into the fact that we have been set apart by God. We understand that we were bought at a great price (I Cor 6:20) and so we offer God ourselves in an attempt at reciprocity. As we pray during the Holy Communion liturgy, “although we are unworthy, through our manifold sins, to offer unto thee any sacrifice; yet we beseech thee to accept this our bounden duty and service” (BCP 81). For Christians, being holy means offering God every part of who we are, not holding anything back, but giving him our whole selves.

The horizontal axis of holiness is also indispensable. “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it; Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” Humans are created in God’s image; if we don’t love others, we can’t love God and vice-versa. Holiness is not an opportunity to look down on others, like in the instance of the Pharisee who uses his perceived holiness to look down on the poor publican. Rather, our holiness should cause us to reach out towards others, to love them better, as a way of evangelism. This was the case for Israel in the Old Testament. Psalm 67 draws out the universal intention of God. He chose Israel so “That thy way may be known upon earth, Thy saving health among all nations. Let the people praise thee, O God; Let all the people praise thee” (vv. 2–3). One of my favorite novels is The Samurai by Shusaku Endo. Without giving too much away, one of the characters performs an act that he knows will bring him martyrdom in Japan. When a puzzled government official interrogates this character as to why he would do something that he knows would bring him death, he responds by saying “Your question itself is the answer. You have said that what I did was ridiculous. I understand that. But why did I knowingly perform such a ridiculous act? Why did I deliberately do something that seems so lunatic? Why did I come to Japan knowing I would die? Think about that that sometime. If I can die and leave you and Japan to deal with that question, my life in this world will have had meaning.” This character makes a peculiar decision for the purpose of Japan’s salvation. The question of Israel’s holiness, and now, the Church’s holiness should be a “splinter in the mind” that causes people to wonder why we act the way we do. That wonder should give way to awe as they grasp the transformative mystery of God’s love and power.

If it’s true that holiness has a two-pronged goal of worship God and bringing the nations to him, the remaining question is how do we become holy. In one sense, at Baptism, you are made holy because Baptism seals us with the Holy Spirit and marks us as Christ’s own forever. Still, holiness is an area in which we can grow as we participate in God’s life. This begins with the grace he gives us at Holy Communion: just like he fed the people of Israel with manna from heaven as they wandered toward the Promise Land so he feeds us with himself as we approach our heavenly destiny. But this is the beginning, not the end. The story that’s played out every Mass should be transposed into our own lives. This happens when we recognize not only who we are but whose we are.

Old Time Bible Hour: Tuesday, August 29, 2023 - St. Gregory of Nyssa on the Life of Moses

The Old Time Bible Hour is a once-a-month session where we look at how Christian who have gone before us read the Scriptures.

Here at St. Paul’s, our Old Testament readings on Sunday are about to take us through the life of Moses. Prepare by attending the Old Time Bible Hour as we read and discuss St. Gregory of Nyssa’s brilliant treatment of the Moses story from The Life of Moses.

Gregory of Nyssa, a prominent figure in the fourth-century Christian church, was born in Cappadocia, Asia Minor, around 335 AD. Renowned for his deep theological insights and philosophical prowess, he played a pivotal role in shaping the doctrine of the Trinity and Christian mysticism. As a theologian and bishop, Gregory authored numerous influential works, delving into topics ranging from the nature of God to the soul's journey toward union with the divine. Without him, we may not have the Nicene Creed. His legacy endures as a beacon of intellectual rigor, spiritual exploration, and devotion to Christ's teachings.

Our discussion will take place on Tuesday, August 29. Evening Prayer will be prayed at 6:30p in the Chapel followed by the discussion at 7p.

August 13, 2023: A Wonderful Episcopal Visitation

A hearty thank you to everyone who made this Episcopal Visitation weekend a great success! Seven confirmations, seven receptions, and one ordination made for a very busy and exciting weekend!